“A More Just and Beautiful World” Through Restorative Practice (Part 2)

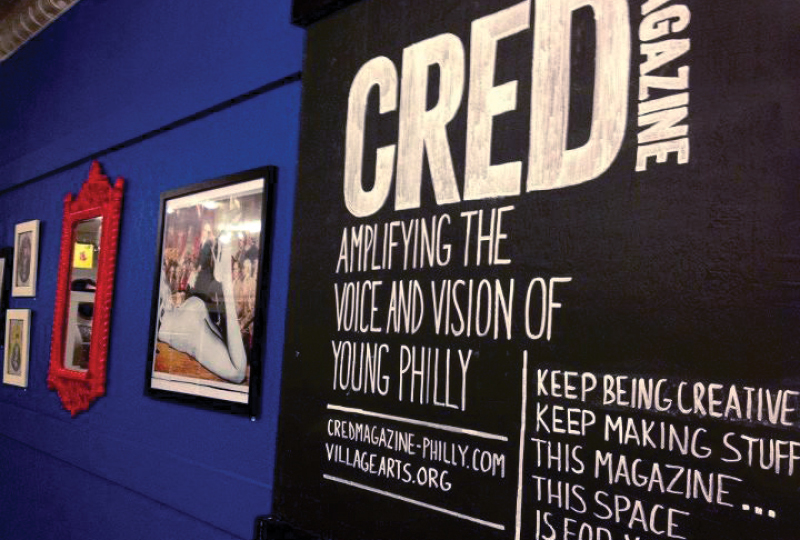

We were lucky enough to speak recently with local cultural practitioners Michael O’Bryan and Mark Strandquist—learn more about these frequent collaborators in Part 1 of our conversation, here. Both work with Philadelphia’s youth, with a specific focus on adjudicated teens and youth within the foster care system. Like our Restorative Practices Youth initiative, Michael and Mark work toward restoring and building healthy communities by increasing social capital, reducing crime, and repairing harm, all through the lens of art, culture, and creativity.

Why is art a good match for restorative practice work?

Michael: I think imagination and creativity are the muscles for growth and change, and I’ve said that 95 million times in the last couple of years, but I really believe it to my core. If we want young people to pursue the best that life has to offer them, that’s an issue of perception—perception of themselves, of trajectories to get to those things, and of those things themselves. My job is to create an environment where youth get to flex and grow those creative muscles. I provide experiences outside of the classroom that help youth transfer those skills and abilities into other domains where it’s not just facilitating the use of the skill—it’s actually building up an interconnected web where they can go be their fullest selves, in all the varying contexts that the world is going to demand from them. It’s not exactly the same as the classroom…that’s one of my biggest roles with young people: getting them to figure out that balance and tension between the world and their actual, fullest selves, and bringing that with them no matter where they are.

Mark: I remember doing a workshop in DC with incarcerated youth, years ago, and asking questions like, “If you were the principal of your school, what would you do to make it a safe and healthy learning experience?” The answers were more police, more security, and more metal detectors, and that’s because it is about imagination, and the world that’s been forced on us. I remember a teen saying to me, “I thought I’d be dead or in prison by 21.” When those physical, emotional, and mental confinements limit our ability to imagine—imagination should not be a privilege. It should be a basic right. I thought the hardest thing about Performing Statistics would be getting a police force in the former capital of the confederacy to allow a group of incarcerated youth to design a training experience for them. The hardest thing ended up being getting the youth to believe that any of it would matter. That’s because they’ve been told by the architecture of their schools and communities, by the way that they’re portrayed in the media, by the way that people interact with them on the street, that their lives are threats, not assets, not resources, not leaders. The other part of flexing that imaginative muscle, what Mike was talking about, is seeing living blueprints. So we ensure that in all of our workshops, there is always a formerly incarcerated mentor, and formerly incarcerated artists. At all times, the youth are seeing that this is not a life sentence. There is living proof. All of us need that at some point, to see where we could be in 10 years. A mentor allows you to teleport into a possible future, and imagining that future is the foundation for other goals.

On moving past paralysis:

Mark: I’m always trying to think about—because these conversations are messy and murky and scary—it’s sometimes easier to think about—especially with students at universities—“well, I can’t touch that. I don’t belong in that space.” I’ve seen people be paralyzed by their fear of engaging in this murky, complex, historically messed-up space, and that’s the worst thing you could do with your privilege. To be paralyzed. In Richmond, what we try to do is to create as many entry points into the work as possible. So no, you young social work student, you cannot come into our workshop space because you’re not ready for that moment, but let’s do an event at your school, or let’s work with your printmaking workshop to make t-shirts with the teens’ designs. There are always ways in which people have assets and resources and skills to bring to the table.

Michael: There’s a whole thing going on right now in the Philly tech community […] it’s this conversation around diversity. It’s interesting because here’s this hard conversation where everyone in the room is saying, “I know everyone’s feeling awkward and we want to move on.” No: sit in the uncomfortableness and have the conversation. The work is already awkward. You’re buying clothes made by prisoners who got locked up when they were 17. It’s awkward. Deal with it. Talk about it. Let’s get to the real work. If you don’t like feeling awkward, then let’s solve it, or at least attempt to get there. I’m not saying that I know how, but let’s unpack it. That’s some stinking stuff. How do we clean this up?

On the upcoming project this spring with Art Ed:

Mark: I’m a deep believer that the process is political. That curriculum and partnership—who is in the room—that’s as important as what you’re producing. I was really excited to be invited into this project [with Mural Arts]. Meeting the teachers that are already working with you in Philly, it was super clear to me that this is a unique group of teachers, because they don’t necessarily come from the traditional pipeline of art educators, and I really appreciated that. I could immediately tell from the kind of questions they were asking, and the kind of projects they were proposing, that these were the right people to be in the room. That’s always the first thing I think about: who’s on the team and who’s missing? My role in this project, as I see it, is a strange place to be as an artist: part consultant, part curriculum development support, part conceptual design and workshop production. We’re super open, but we’re basing the project on exchange with youth on the outside who also have experience within the foster care or criminal justice system. One of the questions is, “What do you need to stay free, and what does freedom mean to you?” We’ve been working with the teachers to come up with an amazing array of mediums, from embroidery to campaign sign installations to audio pieces—

Michael: Every movement needs music!

Mark: The idea is that this fall and spring, we’ll do a series of workshops in different facilities that work with youth within the system, across the city. And then we’ll have a culminating event in the spring where the teens’ artwork will create this stage and space to bring different stakeholders, youth, advocates, into the room at the same time—so the conversation is framed by the teens’ dreams, desires, and demands for a more just and beautiful world.