Public Health and Public Art (Part 1)

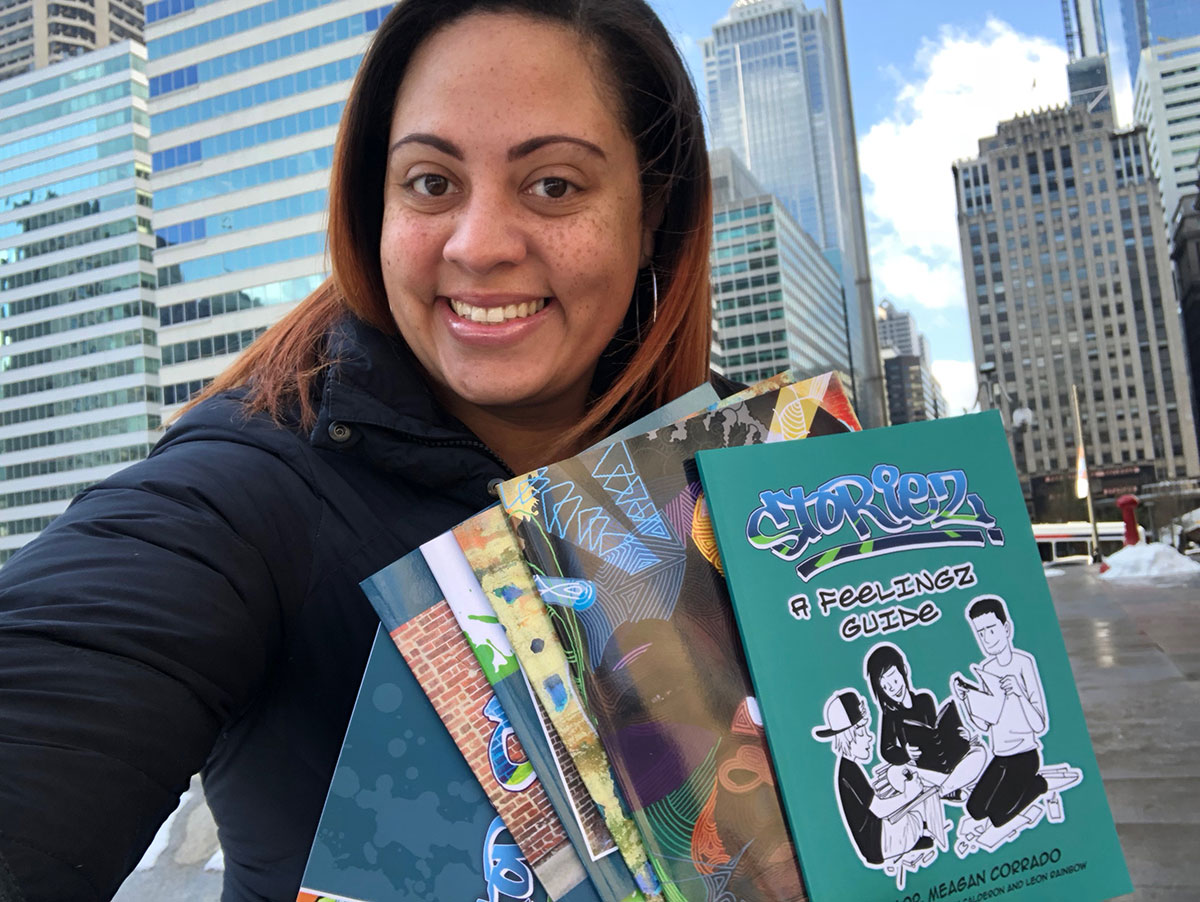

What does community wellness look like, and how can we build it through the arts? These are the questions that Laure Biron and Dr. Meagan Corrado are trying to answer. Biron is the Director of our Porch Light program and Corrado is the founder of Storiez, a trauma-informed creative intervention, and both are Licensed Clinical Social Workers. We brought them together to talk about this new, growing practice that looks at creativity as a mental health resource.

Both of you work at the intersection of the clinical and the creative. Is there a name for that type of practice?

Meagan: It’s this niche that you create for yourself where you’re taking what you know clinically, as it relates to social work theory, and you’re trying to integrate what you know about the fact that the arts are healing, even if there isn’t a ton of research surrounding it.

Laure: What’s been interesting for me—coming from a clinical and an arts background—is that we look at art as a therapeutic intervention at two different levels: how can we work with an individual or a group of individuals around healing through art, and then also how can we improve public health outcomes through the arts? So we do have evidence on some of the levels, but there’s no name for it and there isn’t other evidence. People are always asking me when they look at the Yale report, “What other evidence is out there?” There really is no other evidence. There’s a little bit of evidence-based practice around art therapy, but it’s different from what both of us are doing. So this is really uncharted territory, and, at the public health level, really uncharted territory. The Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services views it as a cost-effective way to treat public health. And I do wonder, if we had a name for it—if all of us working in it could come together and figure out a way to formalize it—if that would help it come together as a field.

Meagan: We’re trying to plan research studies, and it’s also difficult because it’s narrative work. It’s qualitative changes. Translating that into something where you can say, “This was reduced by 40%” is really difficult, but there are all these rich, qualitative, transformational changes that are happening. You’re trying to fit a round peg into a square hole. It’s very organic and flexible and fluid, and it’s there.

Laure: And that change takes a long time, much like with any other therapeutic setting. What you were just saying, Meagan, reminded me of when we were having this presentation on the Yale study, and there were lots of people there that had been through the Porch Light model as participants. At the end, we did a Q&A, and some of them stood up and said, “This evidence doesn’t bear out anything about my experience. My experience is that it [Porch Light] completely changed my life—I no longer identify as an addict, I identify as an artist, and art changed the way that I approached life.” So we know that that evidence exists, and it’s just figuring out how to back our way into some data that we can use.

Meagan: Or change the view of what “data” is. To be able to say that these narratives, these anecdotes, these qualitative changes, are just as important as the numbers in looking at progress and growth.

Are there any other programs or people out there that you consider models for this kind of work?

Laure: There are programs now that have replicated the Porch Light provider site model in Wisconsin and New York City, and a couple of other cities have approached us saying that they’re interested in replicating the model. So there are some that look to us as a model, but when Mural Arts was first designing Porch Light, there were not as many models as you would hope. Participatory public art-making in the mental health field—there was nothing that specific happening elsewhere then.

Meagan: The examples I can think of are either clinical-based work without an arts component, or community arts work without a clinical component. These worlds are in silos. Whenever there’s integration, people think it’s amazing. When I’m talking about this fusion of the two worlds during Storiez presentations, people get excited. It’s something that people intuitively know is important, but there aren’t a lot of people figuring out a systemic way to integrate the clinical and the creative.

Laure: I remember when I heard about your dissertation work, a while back, I thought, “That’s so brave.” To be that deep in the clinical world, working at that intersection—it is hard to work in multidisciplinary settings! Everyone’s in their own camp, and everyone knows what they know, and it requires understanding what you don’t know—being open to other people’s perspectives and what they invite into the room. I think people are open to it—I just think that it’s hard work developing the intervention. It’s tricky to get everybody on board, to help everybody understand the boundary of their own practice, and to help people move from “That’s exciting and new” to “This is how we can actually collaborate.”

Meagan: There’s a lot of fear in interdisciplinary work, because you don’t know what the other person’s goals and professional identity are. You know what your own are, but it’s scary to mash things together. There isn’t necessarily a precedent—are our professional identities going to clash? Are our goals the same? Will we service youth and trauma survivors in the same way, or will there be a dissonance? Fear keeps us separated, when really, integrating our work gives it that much more power, influence, and impact.

Laure: There’s also a lot of fear about expanding the boundaries of these fields. People get nervous: “This looks too much like art therapy” or “This looks too much like the arts.” A lot of people ask me, “What’s it like to work outside your field?” And I don’t work outside my field. This is my field. There’s an anxiety that if you invite other fields into your work, they will chip away at your validity. I have to remind people on a regular basis that I’m a clinician, working through the arts with a clinical mind.

Meagan: Therapists are not the only people that can help people heal. But part of the anxiety is that as clinicians, we often feel that we are the only key to healing. And with the community-based programs, even if there isn’t an arts component, there’s a suspicion about clinicians! “They’re going to get into your mind! They’re going to bring the system into your life! They’re going to sabotage everything that you have going!” It creates barriers when really, we’re trying to do the same thing, and the territory is not limited. We’re the ones limiting it.

Laure: With community-based programs, the value that they bring is that we want to intervene before folks actually need intensive clinical attention. How can we improve behavioral health outcomes in a way where people in the community never need to visit me in my role as a clinician? That’s good public health, because you’re lowering costs overall for both mental and physical healthcare; you’re encouraging folks to get care early on in the process, rather than late in the game when they may need more intensive, more expensive services. It frees up those of us who work in the clinical space to work with acute clients who couldn’t have been intervened upon at an earlier point, or who need a higher level of care. If we can do that in a way that’s not clinical, that’s focused on what the community needs and wants, that’s when we’re all winning.

Porch Light is a joint collaboration between Mural Arts Philadelphia and the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services.